Understanding Wilderness

An Introduction to Wilderness

The 1964 Wilderness Act is one of the noblest legislative acts in history. Most mountain bikers believe the Wilderness Act is well intended and support the notion that wild areas should be protected from construction of roads and development. We enjoy riding in healthy natural environments without substantial human impact. Wilderness preservation has perplexed mountain bikers since 1984, when the U.S. Forest Service prohibited this form of non-motorized recreation from all designated Wilderness areas.

IMBA's guides explores a number of options for protecting nature and bicycle access. They are intended to assist the mountain bike advocate in understanding and becoming involved in a Wilderness and public land protection campaign.

It should be noted, however, that we do not discuss the option of allowing bicycles in designated Wilderness. While IMBA challenges the blanket prohibition, we have not worked to revise the decades-old interpretations by the Forest Service (USFS), National Park Service (NPS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) that ban bicycles from Wilderness. IMBA's efforts have instead focused on maintaining access to significant bicycle routes when new Wilderness is under consideration.

What is Wilderness?

A review of several sections of the 1964 Wilderness Act will help you to understand its intentions, guidelines and scope.

The act begins:

In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.

Congress defined Wilderness:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.

The original Act designated 54 Wilderness areas on national forests and specifically directed the federal land agencies to administer these areas "for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness."

Who Manages Wilderness?

Since 1964, Congress has dramatically expanded the number and extent of Wilderness areas. The National Wilderness Preservation System, as of 2010 includes 791 Wilderness areas encompassing 109.5 million acres managed by four agencies: Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), National Park Service (NPS), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

The two largest federal land agencies, the BLM and USFS, also manage the most Wilderness areas. Because their non-Wilderness lands have been predominantly used for mineral and timber purposes, we often see Wilderness campaigns involving land in these two agencies.

There are several ways to find out about current Wilderness issues in your region and across the country. A phone call or visit to the federal land agency office nearest you is a good way to learn about current and planned Wilderness.

Bicycles and Wilderness

Wilderness often presents a dilemma to the environmentally conscious mountain biker. While most of us applaud the intentions of the Wilderness Act, we also believe that cross-country (XC) style mountain biking is an appropriate, quiet, human-powered activity that belongs in Wilderness alongside hiking and horseback riding.

But why did bicycles ever become embroiled in the Wilderness debate? Note that bicycling is not mentioned in the Wilderness Act. The key provision often debated is in Section 4(b), which prohibits all motorized travel and equipment and allows "no other form of mechanical transport" in designated Wilderness areas. What does the term "mechanical transport" mean? Because Congress did not provide a definition the agencies responsible for implementing the Act have broad discretion to define the term on their own.

In 1984 the USDA Forest Service changed the definition of mechanized so that "[P]ossessing or using a … bicycle" in a designated Wilderness area is prohibited. That early reaction to the infant sport of mountain biking was one of the first to ban bicycling on public lands and was followed by the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service and the US Fish & Wildlife Service, all the other agencies that manage Wilderness.

How are Wilderness Areas Designated?

In order for an area to become designated Wilderness Congress must pass an act declaring the area to be suitable for designation and declaring the area as Wilderness. Because Congress makes the designation the agency is bound to follow the Wilderness Act and any special provisions that Congress has included in the particular designation and the designation cannot be removed or altered except by another act of Congress. In debating a Wilderness bill Congress itself often relies on the state's delegation (both senators and district representatives) for an indication of local support. The importance of this delegation's opinion cannot be overemphasized.

Because it is very difficult to pass a bill of any sort, Wilderness bills often must survive several sessions of Congress before becoming law. If both houses pass the bill, it then must receive the president's signature and become law. It is essential that the state's congressional delegation show near unanimous bipartisan support for a Wilderness bill to pass. In forming their opinions, congress members gauge whether local interests also come out strongly in favor of Wilderness designation and base their support on local city and county endorsements.

The lesson to remember is that, other than committee chairs, the influential Congress members are from the state(s) with proposed Wilderness. These people look to the state and local sentiments in forming their decision on a Wilderness bill.

Wilderness Stakeholders

A majority of the American people support existing and additional Wilderness designations and most bicyclists share these feelings. Unfortunately, most people do not know that mountain biking is prohibited in Wilderness areas. For this reason, it is imperative to reach out to as many stakeholders as possible and let them know that while you may agree with the idea of Wilderness, the ban on mountain biking necessitates your involvement in negotiations before supporting a Wilderness bill.

In any Wilderness campaign there are likely to be numerous groups in favor or against the proposal. Some of these groups may be in favor of Wilderness in one campaign but against it in another. It is therefore impossible to nail down a consistent stance from many groups and describing a groups' position requires very broad generalizations that may not always be true.

IMBA's Wilderness Strategy

Our public policy and advocacy efforts will focus on future Wilderness proposals and recommendations where mountain bike trail access could be lost, where viable alternative land protection designations are appropriate and where local IMBA chapters are present to perform volunteer trail stewardship and engage in advocacy efforts. IMBA will continue to respect both the Wilderness Act and the federal land agencies' regulations that bicycles are not allowed in existing Wilderness areas. This 2016 position strategically aligns with our well-established and relevant mission to create, enhance and preserve great mountain biking experiences.

When proposed Wilderness areas include mountain biking assets and opportunities, IMBA advocates for and vigorously negotiates using a variety of legislative tools, including boundary adjustments, trail corridors and alternative land designations that protect natural areas while preserving bicycle access. IMBA can support new Wilderness designations only where they don't adversely impact singletrack trail access for mountain biking.

How is IMBA Navigating Wilderness?

Updated Fall 2017

At the National Level

There's something called "recommended wilderness" that the U.S. Forest Service can create on its own and that requires no input from Congress. The Forest Service can manage these areas as they see fit, and that management is inconsistent across the country. In some areas (notably Region 1, which includes Montana, North Dakota and northern Idaho), recommended Wilderness is being managed as actual Wilderness, banning bicycle use, despite there being no reason for this.

IMBA strongly opposes this, which is why it made up a large part of our testimony. We have seen 800 miles of trails closed by these bureaucratic actions in recent years, so we're taking this issue straight to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Chief of the Forest Service. We recently sent them a letter regarding our opposition to this management style and why we think it should be changed. We heard back from the Secretary of Agriculture and he connected us with the Chief of the U.S. Forest Service for further discussion on this topic. If we are successful, IMBA could restore hundreds of miles of trail access and directly prevent the loss of even more.

IMBA is also one of the leading supporters of the Recreation Not Red Tape Act—bipartisan legislation that would not only make it easier to develop new trails on public land, but that would expand the number of areas where mountain bike trails are allowed.

And finally, when we see Wilderness (or other land designation) efforts coming together that could impact trails, we make sure that mountain bikers are at the table. And when mountain biking voices aren't heeded, we fight to defeat that legislation. IMBA opposes Wilderness-designation proposals that hurt trail access for mountain bikers. Nothing has changed here. IMBA has been and continues to lead the fight for trails and access for mountain bikers.

At the Local Level

By proving to be truly collaborative partners, IMBA has shown that there are ways to get Wilderness boundaries altered to restore lost trails. Where we aren’t able to be directly involved in these negotiations, we do our best to support out partners on the ground. Here are three recent examples:

In New Mexico (Columbine-Hondo Wilderness), we worked with local mountain bike organizations and moved a 1960s-era Wilderness boundary to allow mountain biking. It set a powerful precedent that we can successfully legislate a modification to a Wilderness boundary. IMBA will work to use that tool wherever possible.

IMBA also crafted a bill currently in the U.S. Senate called the Blackfoot-Clearwater Stewardship Act that preserves bike access to 30 miles of trails in Montana, while also protecting additional acres of land. The local mountain bikers were supportive of this collaborative proposal because the other option, had mountain bikers not been involved, was a total loss of trail access for bikes.

Also in Montana, during negotiations over the Rocky Mountain Front Heritage Act, mountain bikers and IMBA recently fought the expansion of a local Wilderness area that could have eaten up 270,000 acres and closed it entirely to bikes. Because mountain bikers got involved, the Wilderness proposal was shrunk to only 67,000 acres, and the other 208,000 was given a bike-friendly land protection designation, instead, thereby preserving a significant amount of access.

Wilderness and Advocacy

Advocacy Options

How can you protect wild areas and maintain bicycle access? What should you do when confronted with a Wilderness proposal that includes areas with valuable singletrack?

IMBA suggests bicycle advocates focus on four options when Wilderness is proposed. You may choose to focus on one option, or develop a proposal using a mix of these four options:

- Acceptable Wilderness

- Boundary Adjustments

- Non-Wilderness Corridors or Cherry-Stemmed Trails

- Companion Designations

Each of these tools are examined in more detail in the sections that follow.

Acceptable Wilderness

Another option available to bicycle activists is to accept part or all of a Wilderness designation. This can often be a wise course of action. Many proposed Wilderness areas do not have trails popular or suitable for bicycling. Often these places are remote and extremely rugged, and sometimes have no trails whatsoever. Wilderness can be the best designation. Bicycle activists should examine the resource use and preservation values of each proposed area and decide as individuals and as groups on a position for each place.

Unqualified support for particular Wilderness areas appears to be a good political tactic. Bicycling is a quiet, non-motorized, low-impact activity and the conservation movement ought to (and usually does) accept bicycling as a good use of land. The Wilderness issue has divided bicyclists and conservation activists. When cyclists support Wilderness, it builds our relationship with conservationists, and this can help us to gain access to other, more significant trails and landscapes.

Boundary Adjustments

The geographic boundary of a Wilderness area is perhaps the single most important aspect of a Wilderness designation. In nearly every case, arguments ensue over boundaries among people with differing interests and concerns. Congress has often responded by excluding areas, or portions of areas, which have high opportunities for oil and gas development, logging, motorized recreation and other uses that are not permitted in designated Wilderness. Wilderness proponents understand this dynamic and often engage in negotiations with land users to draw boundaries that will not cause substantial political opposition.

The same processes can occur for bicycling. Consider the idea of boundary adjustments to be a process of giving a little to get a little. You may give up a trail or area of little recreational value to mountain bikers to protect a trail or area with substantial riding value. Be realistic in understanding that this compromise will likely be necessary to create a viable Wilderness proposal. Wilderness advocates will be giving up a boundary adjustment so they can protect another area.

Probability of Success: Boundary negotiations are more likely to succeed where the land in question is at the edge and is a small percentage of the proposed Wilderness. For bicycling access, it is also important to demonstrate that the area we want to exclude includes a trail that is already significant for bicycling, or holds the potential for developing a trail that will become important to biking. The political reality is that we should not expect to succeed in a boundary negotiation if all we can offer is a vague idea that someday a piece of land might be nice to ride.

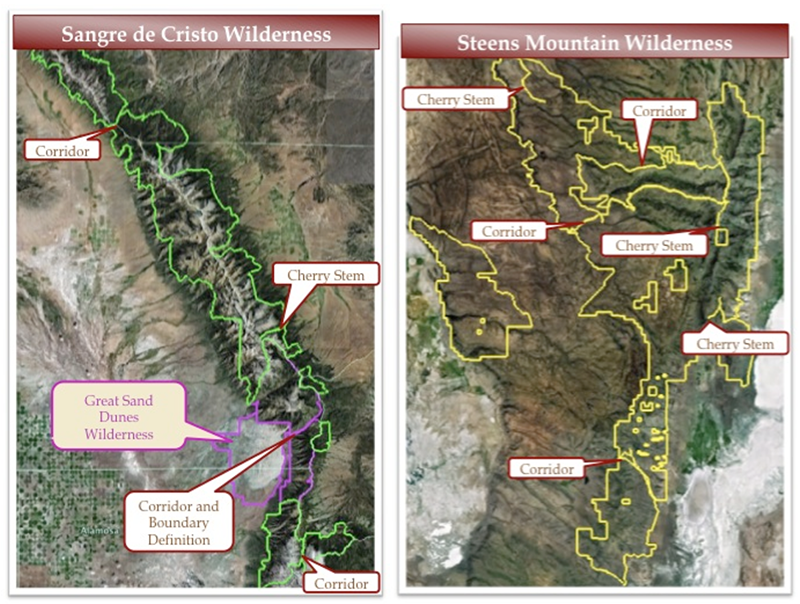

Non-Wilderness Corridors or Cherry-Stemmed Trails

Corridors and cherry stems (collectively Corridors) refer to the practice of defining Wilderness areas to allow non-Wilderness uses to continue on the edge of, or in small area surrounded by Wilderness. Corridors are often used in Wilderness to allow continued access for motorized use, mining, electricity generation and transmission facilities, airstrips, water management and ingress and egress to private property inholdings. A Corridor could also be used to allow continued mountain bike access.

Corridors are used in Wilderness areas managed by all of the agencies that manage Wilderness. Corridors offer flexible management because the trail can be moved in response to natural disasters, reroutes and other unforeseen occurrences. Generally Corridors are just shown on the maps, however, the language in the Wilderness bill could ask for non-Wilderness designation on the trail name itself and 50 feet to either side and be shown on the accompanying map.

Preserving mountain bike access with a Corridor provides recreational opportunities that have minimal impact on the Wilderness area surrounding the trail, while protecting public lands.

Probability of Success: The main advantage of a non-Wilderness corridor or a cherry-stemmed trail is that it doesn't take away a lot of land; only a few acres are effected. This in theory should make it a very enticing negotiation tactic for mountain bike advocates. The moveable nature of the corridor protects it from future unforeseen changes in route.

Companion Designations

Wilderness designation is not the only way to protect land. Congress has used a variety of designations to protect lands for recreational, historical and conservation purposes. Congress has designated lands as national parks, national monuments, national seashores, national conservation areas, national recreation areas, national scenic areas, national wildlife refuges and many other titles. This idea is not new. Many of these designations predate the Wilderness Act and actually blazed the trail for it.

Wilderness supporters advocate for Wilderness designation because they feel it is the most effective. In some cases they may be correct, but legislation for other designations can be drafted to fall anywhere along the preservation spectrum and made to fit the needs and desires of the local people.

If you support a non-Wilderness designation, your proposal should state what management rules would apply within the new area. You can even suggest language that would be in the law designating the area or in the official management plan developed after designation. You may also wish to investigate whether other user group(s) would back your proposal and present it with their support.

For further information about companion designations please see our Companion Designation Toolkit.

Field Research

To find a solution for a particular piece of land, you need a detailed understanding of the area. Volunteers must conduct research, talk with appropriate people, especially land managers, and visit each place to get a better idea for which alternative is best. Groups benefit from having more than one person evaluate each area. After these field investigations, research and observations will need to be compiled and a discussion should be held to formulate a position on each area in question.

Each volunteer who visits these Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) should ascertain whether or not the area is suitable or popular for mountain bicycling, and make judgments about what positions IMBA and local organizations should take. Final decision-making by IMBA and the local organization should involve the field investigators.

Here is a list of information you should consider obtaining before your trip and bring with you on your field investigation:

- Topographic maps: "Topo" maps are necessary to accurately define boundaries and they will greatly assist you when you visit the area.

- Wilderness proposal: Try to obtain a copy of the Wilderness proposal.

- Agency information and recommendation: Inquire with the relevant agency, usually the Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management, and request the information they have on the area. Be aware that the conservationists and agency may disagree about boundaries. Become familiar with the different boundaries proposed and examine the maps to see how those differences affect trail access.

- Recreation guidebooks: Do any recreation guidebooks cover this place? Do they recommend any bicycling in the area?

In the field and afterward, try to answer the following questions for each area. If you are unsure, take your best guess. Some of the questions are simply a matter of opinion.

- Do any mountain bike trails in the proposed area appear in guidebooks or on recreation maps?

- Does mountain biking currently occur within the boundaries of the area? If so, how much? On what trails?

- Are there existing two-track or singletrack trails that are suitable for mountain biking?

- If there is riding currently occurring, is it suitable for: beginners, intermediates, advanced, or only expert riders?

- Do you agree with the assertions in the conservationists' Wilderness proposal? Are there any resources or human developments not mentioned in the conservationists' proposal? Have they chosen a suitable boundary?

- Do you think that the area is meets the basic qualifications for Wilderness designation? (See the definition in Chapter 2)

- Do you think the area should be designated Wilderness? Would you support Wilderness if there were boundary adjustments for particular biking trails? Should it receive some other designation?

- Does the local business community currently benefit from mountain bikers?

- Are there threatened, endangered, or rare native species near trails in the area? Wilderness and other land protection proposals should always protect these resources.

Formulating a Position

To successfully advocate anything, you must first have a position and a goal. Group positions and goals have much more power and advocacy is very difficult when people of similar viewpoints have different positions. When approaching Wilderness issues, mountain bikers should always try to formulate group positions and goals to speak with one united voice.

To formulate a position, bicyclists who know and care about proposed Wilderness areas need to meet and decide how to approach the issue. This meeting should occur after people have adequately investigated each area proposed for Wilderness. For each area, the group needs to choose which outcome they want: Wilderness, Wilderness with boundary adjustments, non-Wilderness trail corridors, and Companions. This decision-making may be difficult process. It will require much communication, and people will need to think about both long-term and short-term consequences.

The positions adopted can be flexible. You might publicly state that you seek an alternative to Wilderness for this area, but you might have a private decision that you could also accept Wilderness with boundary changes. Know your public position, your bottom line, and your fallback position. If the area is not of great importance to mountain bikers, you can adopt a formal "neutral" position. Neutrality can also buy you the time to create your own proposal.

If you desire an outcome other than Wilderness designation, you will benefit from development of a formal proposal. Your proposal can state what boundary changes are needed, or what companion designation is desirable. If you support an companion designation, your proposal should state what management rules would apply within the new area. You can even suggest language that would be in the law designating the area or in the official management plan developed after designation. You may also wish to investigate whether other use group(s) would back your proposal and present it with their support.

Negotiations

After formulating a position on each proposed Wilderness area, bicycling advocates should negotiate with Wilderness proponents, and other interest groups, to see if common ground can be reached. Sometimes we can find win-win solutions that greatly enhance the likelihood of issue resolution.

When negotiating, you must come to the table with an honest and open mind, ready to listen to the other parties' viewpoints. You must respect other parties as you would have them respect you. Listening and respect are more likely to produce successful outcomes than stubborn insistence on unrealistic viewpoints. Taking this into account, though, you shouldn't refrain from asserting your own viewpoint and objectives. If negotiation is done well it will build respect for bicycling and bicyclists.

When entering negotiation, don't expect immediate results. Occasionally, a single session suffices, but more often it takes several meetings. Sometimes, it becomes a grueling, long process.

Do not feel obligated to come to agreement. If you do agree you will have greater chance of success, but there is no guarantee of success, nor is it always necessary. Other people and forces outside the negotiation process can influence votes of Congress. Your negotiation with others can only influence, not control, the Congress members' votes.

In some cases you may find that your best attempts at forming relationships and coalitions fall on deaf ears. If no one is willing to cooperate or make even small concessions for mountain bikers, you may certainly consider formally opposing the Wilderness proposal. This is a position many mountain bikers may be hesitant to take because of their environmental beliefs, but certain situations can necessitate it. Use your opposition to push for negotiations and a revised proposal that has a better chance of being passed into law. Keeping a professional open dialogue, even though you may agree to disagree, is most important. It is critical that cyclists have a seat at the table and are part of the negotiations. Once the door is shut and you have alienated the decision makers, you will find it next to impossible to affect change.

Lobbying Your Position

Whether you have reached a mutually beneficial position with Wilderness advocates or you are presenting your own alternative you will need to get that information into the hands of decision makers and decision influencers. The final decision on Wilderness designation is in the hands of U.S. Congress, but local government officials and local business interests heavily influence their decisions.

Gaining support for your proposal from county commissioners is a great place to start. County commissioners are easy to approach. As you gear up your campaign, find a way to have one-on-one conversations with them. For example invite them to have a cup of coffee, go on a ride or even hike the area in question. You will need to show the county commissioners that a substantial number of local residents support your position with petition signatures or voter letters.

Your campaign to influence the county is an indirect route to influencing your members of Congress. The political efforts you employ at the local level will translate to effective politics at the state and national levels as well.

Talking to members of your state's legislature can also be very beneficial. One effective strategy is to ask the state legislature to pass a resolution regarding its stance on additional Wilderness areas that also references mountain bikes. West Virginia's state legislature has passed such a reference expressing its concern over Wilderness' impact on recreation. This isn't a binding law, but it certainly sends an important message to members of the U.S. Congress.

Another important group are local business interest such as tourism bureaus and bicycle companies and shops. They can be powerful allies and help to spread the word to other cyclists.

The final outcome of any Wilderness proposal will depend on Congress. Only Congress can designate Wilderness. Ideally, you will obtain the support of mountain bike access from both state senators and of the representative(s) whose district(s) includes the areas being considered for Wilderness.

Your objective with each Congress member should be to not only gain his or her support for your position, but also to get a commitment that he or she will support that position in a bill. If just one of the three critical members (one of the senators or the local representative) makes this commitment, you have an excellent chance of success.

Generally, before talking to a member of Congress, garner all the support you can, and muster facts and arguments in support of your position. This issue is not a personal issue for them, it is about policy. Explain why this is good for thousands of people, how it will benefit the local or regional economy and how it will protect the natural environment will help convince them to support your proposal.

Crafting Resolution

Success may be a long time coming. Wilderness proposals do not proceed quickly and it may take several sessions of Congress before a bill passes. After an election, you may need to build trusting working relationships with new elected officials or deal with changing political climates. During periods when little is happening in Congress on the Wilderness bill you're working on, you should occasionally write to your state's Congressional delegation to reiterate your concerns and keep them apprised of any related events or developments.

Some day, the bill you've worked for will pass. When that happens and you succeed, celebrate the win and go riding!

Then be sure to write letters expressing thanks to the Members of Congress, their staff and anyone else you worked with. It is important to also write courteous, appreciative letters to those with whom you disagreed. Such communication will be important in the long run.